There have been many stories of doom and gloom for educational institutions over the past several years. I can’t quite place it, but I expect it probably coincides with the intersection of the mainstreaming of MOOCs, the depths of the financial recession, and the heights of our collective student loan indebtedness. I never quite believed the magnitude of the hype surrounding the negativity, but nevertheless speculation has run wild about the demise of higher education as we know it. The interesting thing to me is that the feelings of defeatism voiced for a period of time by higher educators appear to have more recently shifted to Silicon Valley, home the very disruptors themselves who were supposed to be saving education. I’m encouraged, too, by recent articles (eg: Pushing Back on the Dismantling of Higher Ed Narrative, Why Universities aren’t Dead….and Won’t Be, Why Is The University Still Here?, Disrupting the Disruption in Higher Education, Why Education Does Not Need Marc Andreessen) that push back on this narrative and provide good arguments in the defense of why colleges and universities will continue to exist long into the future despite the increasing pace of change and unforeseen influences of disruption. Nevertheless, there are, in my opinion, some hard realities to consider, particularly for small colleges and universities who are struggling with financial sustainability and continuity challenges. While college isn’t going anywhere, it is likely that some colleges will disappear (and indeed some already are.)

There are a lot of schools

The first reality to consider is one that I’ve surprisingly not seen mentioned until recently. The US has, by-far, the highest number of higher education institutions per capita of any other developed country. Doing some back-of-the-napkin analysis, at best we have roughly triple the number of institutions compared to the next nearest country (which by my count is Canada). At worst (depending on who’s counting and how “university” is defined) we have 5 times as many. The US however, arguably, also has the highest demand (including international demand) for higher education services of any country in the world, but is this enough to justify the existence of so many institutions?

| Country | Population | # Universities | Ratio: university TO person |

|---|---|---|---|

| India | 1,290,000,000 | 298 | 1 : 4,328,859 |

| China | 1,360,000,000 | 574 | 1 : 2,369,338 |

| Australia | 24,000,000 | 87 | 1 : 275,862 |

| Germany | 81,600,000 | 330 | 1 : 247,273 |

| UK | 64,000,000 | 262 | 1 : 244,275 |

| Canada | 35,000,000 | 176 | 1 : 198,864 |

| US | 322,000,000 | 4599 *WA count 7540 *IPEDS count |

1 : 70,015 1 : 42,706 |

Data Sources: Wolfram Alpha, IPEDS

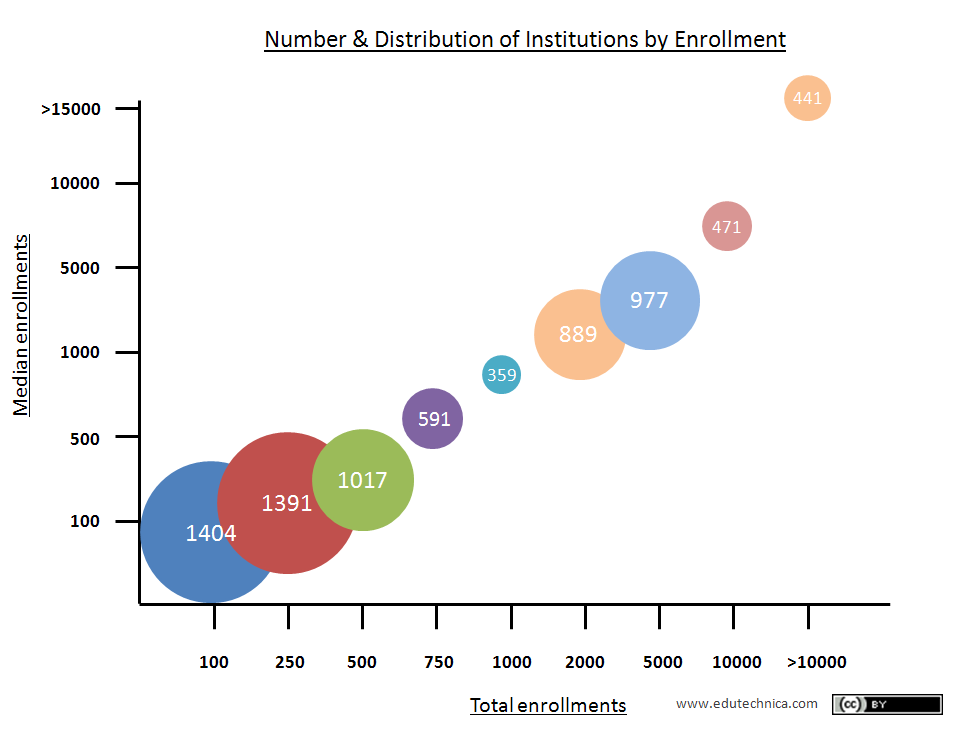

There are a lot of really small schools

A second consideration is that a significant number of these institutions are very small institutions with 500 or fewer students (by 12 month unduplicated headcount). In fact, a disproportionately large number of colleges and universities have fewer than 250 students! That’s a lot of small higher education institutions whose total size is smaller than a fair number of high school graduating classes. As the owner of any small business knows – competition is constant and fierce. As the head of any small non-profit knows – it’s hard to do much without the resources.

Data source: IPEDS 12-month FTE enrollment: 2012-13 (Source: IPEDS, select “Use final release data,” then “By Groups->EZ Group,” then “U.S. Only”, n = 7540 accounting for records indicating 0 enrollments)

Making finances work is challenging for small organizations

Another major reality is that a lot of smaller colleges don’t have endowment funds to support and invest in themselves during difficult times. Well-endowed schools also have the good fortune (no pun intended) to do good things with their funds during good times like guarantee scholarships for brilliant students who otherwise may not be able to afford tuition costs. If you add up the endowment funds of all US institutions with under 500 students – that is, all 3272 institutions of this small size combined – the total would only be 1/4 the size of Harvard’s endowment alone ($8,218,582,555 to $32,012,729,000). While endowments have probably gone too far at some schools, small schools instead rely heavily on tuition as a primary and often only source of funding. They don’t often have research grants or technology transfer agreements or sports trademark licensing profits that diversify their revenues.

Many smaller colleges are actually being monitored by the Department of Education specifically because of the potential for looming financial troubles thereby placing additional regulatory burden on them. Cash flow is more important than many realize (unless employees are willing to work at times for free and supplies can be acquired on loan). The hard reality is that salaries and bills need to be paid, and a one-time campaign for donations is not likely to stabilize a university’s core finances in a sustainable way (unless you happen to get really, really lucky). (By the way, at only a 5% interest rate, $400 million generates $20 million in returns every year ad infinitum. $20 million in free money, every year!)

Not doom & gloom, but change is necessary

While the realities may seem insurmountable, I believe that they are for many reasons. While the percentage of college-aged students is trending down, the overall number of potential students looks to be expected to increase. Higher learning is becoming more popular in later life. Nanodegrees and bootcamps may offer spurts of learner engagement throughout life instead of only once or twice. (It’s bizarre to me that while most companies attempt to cultivate lifelong relationships with customers, higher education lets theirs literally walk across the stage and out the door.) Employers are beginning to fund education as a benefit. Technology is not only a threat but can provide tremendous opportunity to reach audiences like never before. And despite all of the craziness in the news, people still love learning. Education is one of those rare possessions that once acquired can’t be stolen or repossessed or taken away. It is not a commodity. And universities provide a level of authority and trust earned over many years. There is a reason the word credential stems from the Latin root word meaning “to believe in” or “to trust.” This is a differentiator that no software startup can match. (In fact, many new edtech organizations attempt to build on the pre-existing reputations of schools, eg: MIT and Harvard for the non-profit EdX, the “elite schools” initial roll-out strategy of Coursera, Udacity and Stanford, etc.) But in order to keep this trust, universities must become more willing to change and adapt. There is some truth to the saying that it isn’t the smartest or largest creature who survives but the quickest to adapt.

I tend to agree with George Siemens when he says to “expect a future of universities being more things to more people.” Though universities have been argued as quick to innovate but slow to change, smaller universities in my opinion are actually in the best position to change and adapt.

As much as I am encouraged to see so much talk about learning model innovations (eg: Competency Based Education and other flexible, personalized, and adaptive options), I am equally excited to see some universities experimenting with business model innovation. Improved learning models promise to improve educational outcomes over time, but business model innovation may very well keep small schools in business today. Some schools like Hodges University (as are some giants like Kaplan) are experimenting with subscription models that offer “unlimited course access” for a period of time. Others are diversifying revenues by more fully utilizing university space and services during summers and other periods of downtime. Small universities are also exploring partnerships, networks, and alliances with each other or through partners such as StraighterLine and ed2go that begin to offer a way to address some of the business partnership challenges and lower transaction costs between universities. There is plenty of opportunity out there and a lot of great ideas. They just need to be explored and executed.

Some small schools though, in my opinion, will have no choice but to explore mergers and consolidation in the future. There are plenty of reasons to consider doing so and plenty of reasons not to. While success is not guaranteed, there are also many success stories to consider.

There is no one root cause and no one way to solve the problems faced by higher education institutions today. Instead there are many ways to overcome our challenges that may be appropriate for different types of schools with different strengths and goals. By better understanding some of these challenges, thinking through options, and proactively pursuing new opportunities, my personal hope is that colleges and universities craft our own futures rather than having change dictated to us. But we have to do it in a way that makes sense to the needs of modern learners.

-GK