Several years ago I joined UMUC because of it’s unique mission – to serve as an open-enrollment, online public university that meets the unique needs of non-traditional, adult learners obtaining their degrees during their nights and weekends all around the world. During the time that I was there, the institution made great forward progress particularly in their use of analytics to reduce costs, reduce drop-outs, and increase new enrollments. The university also launched a new online learning environment, transitioned to using no-cost digital course materials and Open Educational Resources to improve affordability for students, and began to work on creating a new, flexible learning model enabled by advancements in technology and learning science. Not only did I have a great experience working for UMUC, I am also a former student as well. While a student, I became the first person in my family to obtain an advanced degree. I was able to do so in my nights and weekends without having to quit my day job or take on large amounts of debt. My classmates included stay-at-home parents, military service members here and abroad, and people like me trying to earn a credential when and as they could to take the next step in their careers. The passion and dedication of the educators at UMUC was always very apparent, and I’m grateful for this experience as well.

This is why I’m very concerned that in the past 9 months, almost half of the university’s Cabinet has turned over, including one of two Deans (the one who was the primary driver behind the new learning model), the Provost, and over half of those representing the academic side of the university including the VPs of academic affairs and student advising and retention. Instead of filling these slots, several new positions have been added to the Cabinet with flashy new business-oriented job titles such as “Vice President, Strategic Partnerships,” “Vice President of Strategy and Innovation,” and 3 different new positions with “Enrollment Management” in their titles.

| April 2016 | Changes in Cabinet-level Leadership |

February 2017 |

| Marie A. Cini, PhD | Provost and Senior Vice President, Academic Affairs | Stepping down |

| Senior Vice President, Strategic Enrollment Management | Erika Orris | |

| Jason Reed | Vice President and Chief Technology Officer | — |

| Allan J. Berg | Vice President and Director, UMUC Asia | James “Jim” Cronin |

| Kelly Wilmeth | Vice President and Director, UMUC Europe | Robert “Bob” Loynd |

| Vice President, Communications and Engagement | Heather Date | |

| Alexa Kim | Vice President, Customer Service | — |

| Vice President, Enrollment Management | Lisa Henkel | |

| Lisa Branic | Vice President, Enterprise Project Management | — |

| Mary Ann Donaghy | Vice President, Marketing | — |

| James “Jim” Cronin | Vice President, Stateside Military Operations | Kelly Wilmeth |

| Vice President, Strategic Partnerships | Ed Bach | |

| Lisa Henkel | Vice President, Student Advising and Retention | — |

| Susie Chang | Vice President, Student Recruitment | — |

| Vice President of Strategy and Innovation, Strategic Enrollment Management | Joseph Cantoni | |

| Aric Krause, PhD | Vice Provost and Dean, The Graduate School | Recently vacated, Kathryn Klose (acting) |

| Marcia Watson, PhD | Vice Provost, Academic Affairs | — |

| Karen Vignare, PhD | Vice Provost, Center for Innovation in Learning & Student Success | — |

There has to be a reason for this level of ongoing churn on the university’s leadership team. This same trend is reinforced throughout the organization, which at the time of this writing had 468 open job positions…which also seems unusually high.

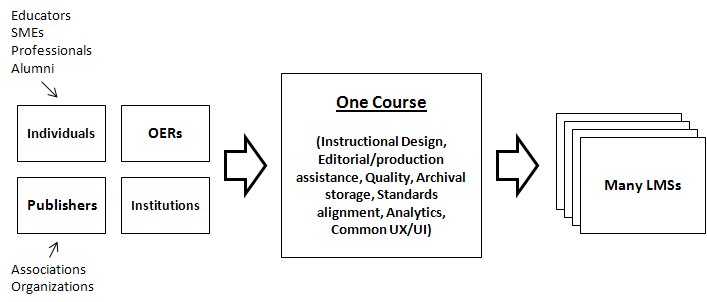

As of the time that I left, my impression is that the university was beginning to struggle with finding a balance between its core mission focused on academics and the business aspects of focusing on future innovation. The noted shifts in the Cabinet membership seem to reflect these changes in priority and focus. As much respect as I have for the university President, he seemed quite enamored with finding ways to use public resources to found private educational technology startup companies – instead of with the core academic mission of the university. The thinking was that the university might use excess income from these startups, or the proceeds from selling them off, to fund scholarships. This is a noble goal, but the business of edtech is extremely risky at best and can result in losing hundreds of millions of dollars for even the largest and most successful educational technology companies.

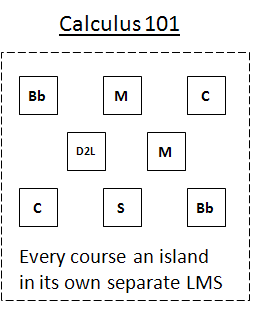

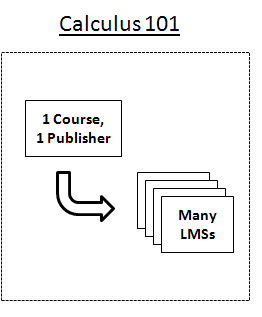

Perhaps, though, I shouldn’t be so surprised by this shift in focus; innovation and adaptation always seemed to be driving characteristics of the organization’s culture. After all, the old homegrown Learning Management System (LMS) that I helped to replace was a relic of a pioneering effort to develop online learning software that was at one time licensed to a handful of other universities – one of the first efforts to commercialize an educational technology product developed at and by a university. While that effort was ultimately shuttered, it was still a success. HelioCampus, an analytics company, is another recent educational technology spin-off that capitalizes on the institution’s analytics prowess. It was created by privatizing the team of 15 (p. 26) full-time analytics experts that were previously state government employees and funding it with $10 million in seed money from UMUC’s own fund balance.

I recently learned from one of UMUC’s IT recruiters that they are again planning to privatize another group of employees and create another educational technology spin-off. This time, they are planning to lay off and outsource the entire university’s IT department to a private company wholly owned as a subsidiary of another company that the university previously created.

“The company will act as holding a company for some of the key services at the university, specifically IT. This will allow the IT organization to be more agile and have a higher impact on students, impact through innovation.”

Recent state budget testimony (p. 24) reveals more about the scope of the effort:

“There is an active discussion underway contemplating the creation of a new education enablement company owned by UMUC Ventures. This company would be formed by spinning off the UMUC Office of Technology, intended to serve UMUC and possibly other institutions”

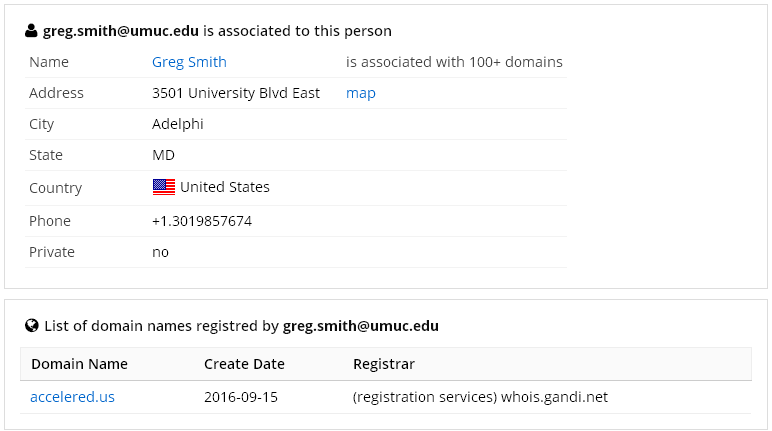

A recent domain name registration even hints at the name of this new company: AccelerEd. The registrant is the current AVP of Enterprise IT Operations according to this LinkedIn profile.

I am very concerned by this development for three reasons. First, this action further distracts the university from its core academic mission. Second, outsourcing the core IT operations for an online university is an incredibly risky move, especially considering the way in which it is being done. Finally, I am concerned by UMUC’s trend towards privatizing public resources.

As a former employee of the university, I was drawn to its unique mission, and many of my former co-workers were, too. Universities like UMUC that offer alternative pathways to better lives play a critical role in addressing the needs of populations not served effectively by more traditional institutions. I now worry about the stability of the jobs of my former co-workers, the impending and unexpected changes to their benefits, and the impact on those more experienced employees – particularly their loss of state pensions through no fault of their own. This change will result in material impacts to many lives. These transitions are never easy and are rarely fair.

As an alumnus of the university, I am concerned about the damage to its reputation caused because of this change in focus. Good employees who disagree with this shift in direction will leave (and as evidenced above, many good leaders already are). Placing IT operations into a different company, whether owned by UMUC or not, will introduce yet another silo between organizations and result in an inefficient and sub-par experience. I cannot think of an example where such an effort has worked well. I welcome any counter-examples.

As a taxpayer of Maryland, I think of UMUC as a state treasure. The university has a special academic mission, and I hate seeing it put on the back-burner. I don’t want to see the great work of UMUC privatized. And if the plan is to outsource UMUC’s entire IT department, I also think this should go out to RFP to be bid upon to obtain the best value and be fairly won. It should not be automatically awarded to a company the university just happens to own. In this mindset, I also think it’s very wasteful for the university to spend $2.7 million of state money (p. 105) in December of 2016 to redesign the 1st floor of its administration building specifically for the purpose of “transitioning the Analytics, Planning, and Technology workforce to a workplace/office of the future” (p. 5-6) when the plan to spin this business unit off into a separate company was known at this time. (The last time this exact same building was significantly renovated was 2013.)

As an expert in the field, I admit that I actually like the idea for this new spin-off company. UMUC is full of great software developers, educational technologists, and instructional designers who have worked well together for decades. It would be a venture capitalist’s dream to commandeer such a capable team to found a startup company. However, I wholly disagree with the approach the university is taking to form this company. There is a significant level of risk for an online university to outsource its entire IT function to a separate entity. UMUC already relies heavily on adjunct faculty and outsourced recruiting and student support. While I have always had concerns about the risk and fairness inherent in these decisions, the IT team runs the technology that powers a fully-online university. There is no UMUC without an online classroom. Any impact to IT’s ability to execute reliably will directly affect students. As a separate entity, there will be even fewer ways for the university to hold this organization accountable, especially considering that the university itself, in a circular way, will be its ultimate owner and financier.

Founding another educational technology company at this time would also be very risky, especially considering that the university’s other existing technology startup has yet to be proven successful. HelioCampus is only expected to reach profitability in 5 years (p. 24) and has only a small handful of customers – almost all of whom appear to be other University System of Maryland institutions (p. 1-2). The university should give HelioCampus more time to prove its success before embarking on another much riskier and more significant effort. Starting too many different efforts too soon could even jeopardize the early success that HelioCampus has had by diluting focus on establishing its momentum.

Finally, as a blogger I’m concerned that we may never learn much more about this effort in order to hold our public institutions accountable for how taxpayer money is spent. UMUC has lobbied for and received specific, special exemptions from the state’s Public Information Act (p. 48-49):

“(a) A custodian may deny inspection of any part of a public record that: (1) relates to the University of Maryland University College’s competitive position with respect to other providers of education services…(ii) a proposal generated, received, or negotiated by the University of Maryland University College, other than with its students, for the provision of education services; or (iii) any research, analysis, or plans compiled by or for the University of Maryland University College relating to its operations or proposed operations”

As stated in the university’s recently updated strategic plan (p. 14), the mission of University of Maryland University College is improving the lives of adult learners. The direction that the university is heading is deeply concerning and squarely focuses the institution on the business of educational technology rather than its academic mission. I strongly encourage the university’s new leadership team to refocus on its core mission. The best way to move forward is to re-align the university’s IT department with its academic leadership, not separate them even more. UMUC has a long legacy of innovation driven by partnerships across academic and technology units, and strengthening these relationships will do more to sustain the future success of the university than severing these deep and historically-successful ties.

This is a guest post authored by George Kroner